The sad tale of Lake Naivasha, Kenya; a mountain of underused knowledge?

13 November, 2024

By David M. Harper, david.m.harper@icloud.com

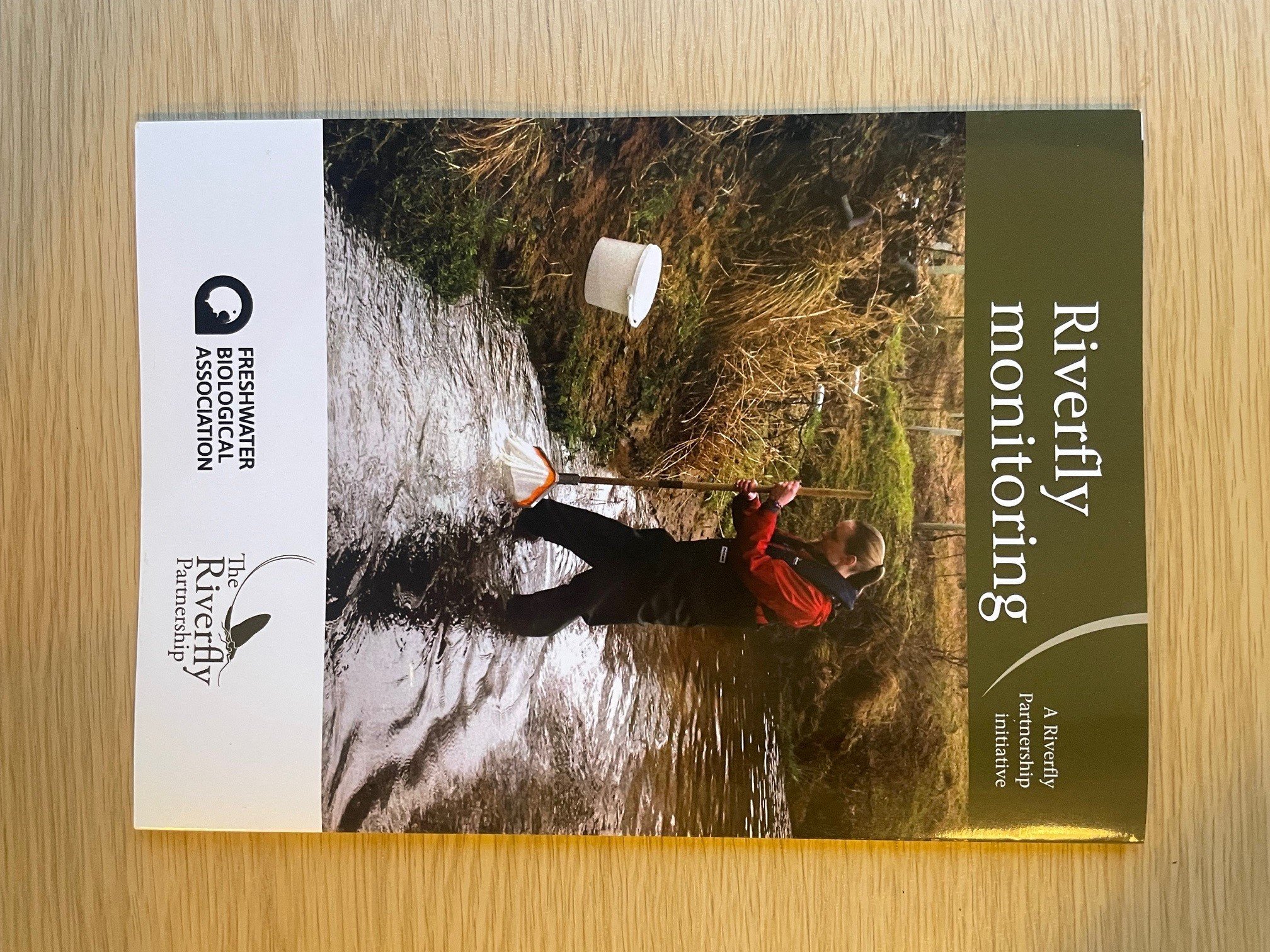

David Harper, Emeritus Professor at the University of Leicester and FBA Fellow, led research in Lake Naivasha for 34 years, starting in 1982. Here, David reviews the past and looks to the future of the lake and its alteration by human pressures.

Edited by Rachel Stubbington, Nottingham Trent University

Rachel is both a Fellow of the Freshwater Biological Association and long-standing Editor of FBA articles. If you would like to submit an article for consideration for publication, please contact Rachel at: rachel.stubbington@ntu.ac.uk

Introduction

There is arguably no lake anywhere in the world that has greater combined economic value and scientific knowledge than Lake Naivasha, a freshwater lake at 2,000 m altitude in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley (Kuiper et al. 2024). Yet, other than Maasai who have known it for countless generations, we have only known of the lake’s existence for 150 years and of its limnology for <100 years.

Early history of the lake

The FBA contributed to the first scientific description of Lake Naivasha, during two expeditions to the East African lakes in the 1920s–30s. A local fish warden had surveyed its fish population, noting a single native species of a small tooth carp Micropanchax antinorii, calling it “of no use to anyone” and recommending introduction of the American large-mouthed bass Micropterus salmoides as a sport fish. That single native fish species had disappeared by 1964.

The colonial government (since 1895) had already allocated land around the lake to white settlers, disrupting the generations of Maasai pastoralists who had used the lake’s waters as a dry-season refuge for cattle. During severe droughts, only one small volcanic crater remained, providing some water alongside the papyrus swamps that provided grazing (Fig. 1). One such drought had occurred in the previous two centuries, hence the depauperate fish community.

Figure 1. Cresent Island Lagoon, the volcanic crater that is the deepest part of Lake Naivasha, photographed in the mid-1980s.

The Maasai had lived in harmony with many bird and mammal species, described by explorers as “one moving mass of ducks with ibises, pelicans and other aquatic birds” (Thomson 1887) and “the whole surface [of the lake] was thickly dotted with coots… an outer border of small lots of yellow-billed ducks, pochards and pink-backed teal… totally unconscious of danger and strangers to a shotgun”… around the lake margins, “beautiful animals thunder[ed] along in the grass in great squadrons” (Jackson 1930).

The white settlers had ideal conditions for intensive farming: equatorial sunshine and temperatures with endless freshwater for irrigation. They grew fruit and vegetables, established dairy farms and cattle breeding supported by irrigated lucerne. They were possessive of the lake, thwarting early attempts to protect it as a conservation area. The Lake Naivasha Riparian Owners Association (LNROA) had been legally established in 1932 to deal with disputes about the cultivation of ‘riparian’ land when the lake receded below a certain level.

During the inter-war years, colonial government hydrologists had struggled to understand the lake’s dynamics and its ‘safe yield’ for irrigation. One puzzle was that it had no outlet, yet remained fresh – unlike other lakes in this Eastern Rift Valley, which were saline through evaporation. Modelling and chemical tracing later demonstrated that a subterranean outflow running along the valley maintained its freshness. Also intriguing were its enormous changes in size in recent millennia. Archaeological excavations led by Louis Leakey nearby had revealed lakeshore camps and tool-making sites many tens of metres above the present lake, and convincing geological evidence of the strand lines subsequently indicated past climatic changes. Detailed changes in past water levels, and hence chemistry and biology, were later demonstrated by analysing sediment cores from the lake’s deepest part.

Following independence in 1963, foreign governments gave substantial assistance to the new Kenyan government, particularly in education. Detailed work on phosphorus and nitrogen movement through the papyrus swamp in the delta of rivers flowing into the lake’s north end made significant contributions to global understanding of nutrient cycling. High plant diversity occurs in the ‘drawdown zone’ between the upper and lower water levels, reflecting unpredictable annual and decadal rainfall. Climate variation produces the drawdown zone and its biodiverse zonations on a decadal time scale, similar to annual-scale riverine flood pulses. The knowledge was such that, in 1979, an 80-page account of the lake’s limnology was produced for a United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Congress in Nairobi, prior to the launch of the World Conservation Strategy.

Beginning of the lake’s deterioration

National and international alarm bells rang from the time of independence regarding the impacts of alien species on the lake’s ecology. First, in the 1960s, Salvinia molesta arrived, a floating water fern which had caused considerable damage in other tropical countries. This was followed in the 1970s by the Louisiana crayfish Procambarus clarkii, and in the 1980s by the water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes (Fig. 2). Initially, damage was perceived as primarily economic, through plant biomass blocking irrigation pumps. By the 1980s–90s, several fish species had been brought in, mostly tilapias from hatcheries. Understanding of the negative impact of alien species and loss of native species increased, generated by collaborative UK–Kenya research.

Figure 2. Proliferation of the invasive water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes, in 2015.

Irrigation became increasingly important during the 1970s–80s, as the vegetable export market expanded to include cut flowers irrigated by water pumped to greenhouses on riparian land. By ~2012, cut flowers worth £260 million p.a. accounted for 70% of Kenya’s flower exports, and vegetables irrigated from the lake and catchment worth £25 million p.a. comprised 20% of national vegetable exports. Together, these exports accounted for 10% of Kenya’s foreign exchange revenue.

As horticulture moved from lake and river irrigation to groundwater and rainwater use, a clear understanding of the lake’s groundwater and surface-water hydrology was emerging. Increased scientific investigations enabled the LNRA (which dropped the “Owners” to recognise the need for conservation) to engage consultants, write a lake Management Plan and pressurise the government to designate it as a Ramsar site, a status it gained in 1995.

Despite this designation, the increasing footprint of the horticultural industry caused lake health to rapidly deteriorate after 2000. Chlorophyll content increased and transparency decreased, due to the development of settlements for thousands of migrants seeking employment in horticulture. Most gathered or purchased lake water for domestic use, and many used the lake for ablutions (Fig. 3). Spatial planning and services for these settlements were non-existent.

Figure 3. Settlers collect water from the lake.

By 2005, water quality was so poor that cyanobacterial blooms occurred, followed by fish kills from low oxygen caused by sediment input and re-suspension by storms (Fig. 4). By 2009, water levels had fallen to their lowest since 1948, exacerbating water quality issues and causing problems for commercial carp and tilapia fisheries. This lake level decline resulted in negative publicity for associated European supermarkets, which coincided with international publicity concerning the poor conditions of horticultural workers.

Figure 4. A street in a settlement after a rainstorm. The runoff and associated sediment and other pollutants drain directly into the lake.

National events impacting upon the lake

In 2007, the Kenyan presidential elections pitched candidates from the two largest tribes against each other. After a corrupt election and disputed outcome, tribal violence erupted. Naivasha and nearby townships were hotspots of the violence, because so many tribes had settled there. The negative publicity of the riots and the risk to the high economic value of Lake Naivasha raised its profile among western governments associated with horticultural companies. An international response included UK input from Prince Charles’ International Sustainability Unit (ISU) designed to advance the lake’s sustainable management.

The low lake levels and political instability motivated financial support from western governments and supermarkets for new social science projects and ongoing limnological research. ISU involvement led to creation of a new umbrella organisation, Imarisha (meaning Arise) Naivasha, to coordinate the many interests in commercial and environmental aspects of the lake and its catchment. Imarisha, only quasi-governmental, raised international funds and began to coordinate meetings, conferences, projects and sustainable management plans. But these plans lacked a major element: none recognised the fragility of the ecosystem and its dependence upon the lake’s unique ecohydrology, and none proposed restoring its degraded state.

Is there hope?

Two examples from Kuiper et al. (2024) illustrate this depressing situation. First, the new constitution, developed post-violence in 2010, devolved power – including of fisheries management – to elected governors in 47 counties. Nakuru County seeks to maximise income from commercial fisheries (fishing boats using gill nets) by issuing >3× the number of licences recommended for sustainable yield – and licence income is not invested in fisheries management. Regulation of licenced fishers is poor and many use 10× the number of gill nets allowed (Fig. 5). Moreover, illegal fishing using fine-mesh seine nets thrown into the shallows has been left unchecked and now takes perhaps 10× more fish biomass from the lake as the licenced fishery.

Figure 5. Illegal fishers use a seine net in the shallow lake waters.

Second, a major railway development reached Naivasha in 2018. The town and its hinterlands are now affected by three associated ‘mega-projects’: an inland container depot, an associated ‘Special Economic Zone’, and infrastructure supported by water drawn from a planned major dam on the river Malewa, which feeds Naivasha. This dam has been proposed since the 1990s, but a mega-dam would be needed to supply planned developments, and would take as much water as flows into Naivasha in an average year. In addition, a geothermal plant south of Naivasha – which already abstracts more water directly from the lake than any other user – continues to expand.

The only glimmer of hope that I see is the rapid growth of young professional scientists in Kenyan universities, research and government agencies, who might be able to bring an environmental balance back into the future economic plans for this wonderful lake.

References

Jackson, F., 1930. Early Days in East Africa. Edward Arnold, London. 399pp.

Kuiper, G. et al. (eds.). 2024. Agricultural Intensification, Environmental Conservation, Conflict and Co-Existence at Lake Naivasha. Brill, Leiden & Boston. 383pp.

Thomson, J.J., 1887. Through Masai Land: A Journey of Exploration Among the Snowclad Volcanic Mountains and Strange Tribes of Eastern Equatorial Africa. Sampson Low, Marston & Co., London. 583pp.

Further reading

Harper, D.M. et al. 2011. Lake Naivasha, Kenya: Ecology, society and future. Freshwater Reviews4: 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1608/FRJ-4.2.149

Further FBA reading

The Freshwater Biological Association publishes a wide range of books and offers a number of courses throughout the year. Check out our shop here.

Get involved

Our scientific research builds a community of action, bringing people and organisations together to deliver the urgent action needed to protect freshwaters. Join us in protecting freshwater environments now and for the future.